Cold Electricity by Edwin Gray

What is Cold Electricity?

In 1958, Edwin V. Gray, Sr. discovered that the discharge of a high voltage capacitor could be shocked into releasing a huge, radiant, electrostatic burst. This energy spike was produced by his circuitry and captured in a special device Mr. Gray called his “conversion element switching tube.” The non-shocking, cold form of energy that came out of this “conversion tube” powered all of his demonstrations, appliances, and motors, as well as recharged his batteries. Mr. Gray referred to this process as “splitting the positive.” During the 1970’s, based on this discovery, Mr. Gray developed an 80 hp electric automobile engine that kept its batteries charged continuously. Hundreds of people witnessed dozens of demonstrations that Mr. Gray gave in his laboratory. His story is well documented in the following materials.

|

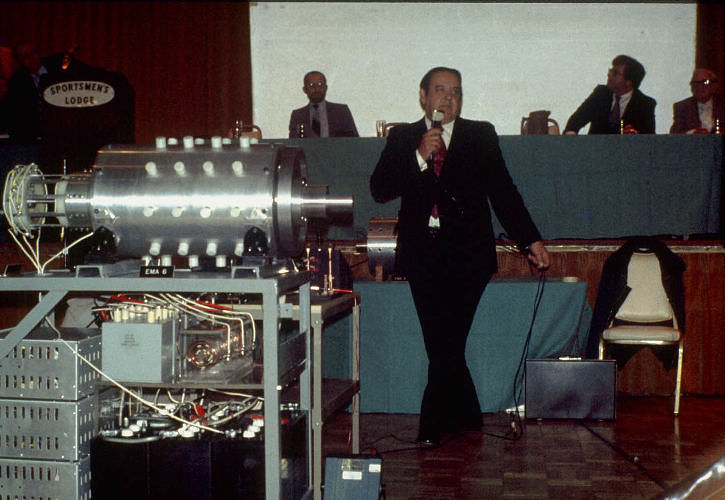

| Edwin Gray performs Cold Electricity to the public and corporations |

"Very interesting (and dangerous) phenomena manifest themselves when the current path is interrupted, thereby causing infinite resistance to appear. In this case resistance is best represented by its inverse, conductance. The conductance is then zero. Because the current vanished instantly the field collapses at a velocity approaching that of light. As EMF is directly related to velocity of flux, i tends towards infinity. Very powerful effects are produced because the field is attempting to maintain current by producing whatever EMF required. If a considerable amount of energy exists, say several kilowatt hours* (250 KWH for lightning stroke), the ensuing discharge can produce most profound effects and can completely destroy inadequately protected apparatus."

"Steinmetz in his book on the general or unified behavior of electricity The Theory and Calculation of Transient Electric Phenomena and Oscillation, points out that the inductance of any unit length of an isolated filamentary conductor must be infinite. Because no image currents exist to contain the magnetic field it can grow to infinite size. This large quantity of energy cannot be quickly retrieved due to the finite velocity of propagation of the magnetic field. This gives a non reactive or energy component to the inductance which is called electromagnetic radiation."

|

| The primary winding of the Tesla transformer is interrupted, suddenly open-circuited with a spark gap design. |

🔹 Version from Nikola Tesla's "Magnifying Transmitter"

🔹 The "tension" for "electricity fractionation" to occur is the Earth's Potential Potential. To be precise, it is the tension of the Ether, and the electricity is the dynamic polarization of the Ether.

🔹 During "Electricity segment", the magnetic field collapses several times in short periods of time. That leads the voltage V = Φ/t to reach infinity (V → ∞) when t → 0

- V - The electromotive force which results from the production or consumption of the total magnetic induction Φ (Phi). The unit is the “Volt”. Where t is the time of magnetic field collapse from maximum to complete collapse.

- Research scholars also call it Tesla's technology called Radiant Energy from Electronic Circuits, Impulse Technology.

Decoding Gray's Patents

I have taken a great deal of time to explain the intricacies of Tesla's Magnifying Transmitter because of how it directly relates to the operation of Ed Gray's cold electricity circuit. To better understand what his circuit is and how it operates, Figure 26 shows Gray's "schematic" on the left, as it is presented in Patent # 4,595,975, and on the right, it shows what I refer to as the "Simplified Gray Circuit `Schematic."' (I'm using the term "schematic" in quotes because this is not entirely a schematic diagram.)

|

| Figure 26 Gray's Circuit "Schematic" and the Simplified Gray's Circuit "Schematic" |

In order to better understand this circuit in its most fundamental form, I would like to eliminate a number of components, temporarily, that serve functions outside of its essential operation, as follows:

- Components # 64 and #66 (shown within the dotted-line box) indicate an alternate way of running the circuit from an AC supply. These parts can be eliminated without changing the circuit in any significant way because the circuit can be run from the batteries

- Components # 42, # 44, and # 46, which are the safety overshoot mechanisms referred to earlier, can be eliminated because we learned in Chapter 1, reading from the patent text, that these parts are included simply to protect the circuit in case it generates too much energy.

- Component # 26, which Gray calls a "commutator," is part of the timing mechanism. However, the vacuum triode, # 28, is sufficient to give us the timing impulses for the discharge of our capacitor, so # 26 can be eliminated.

- Component # 48 is a switching mechanism that allows the operator to change which battery is powering the circuit and which battery the circuit is charging. This can be eliminated by simply indicating that battery 18 is running the circuit and battery 40 is receiving the charging impulses.

- They both start off with a source of high voltage direct current. In Tesla's case, it's a high voltage direct current generator, Source "B". In Gray's case, it starts with a battery, # 18, whose output is chopped through a multi-vibrator, #20. The impulses coming from the multi-vibrator power the low voltage, primary winding on transformer #22. The high voltage secondary winding of # 22 is then rectified with the full wave bridge, # 24. The output from # 24 is high voltage DC. But either way, both circuits begin with high voltage DC.

- The next component in both circuits is the capacitor. In Tesla's circuit it is "C"; In Grays, it is # 16. Both circuits operate by having the capacitor charged repeatedly by the high voltage DC source.

- The next component in both circuits is the spark gap. In Tesla's circuit it is represented as "d-d". In Gray's diagram it is # 62. For each circuit to work properly, the spark in the gap must be characterized by two features: first, there must be a means to insure that the discharge will occur in only one direction, and second, there must be a means to control the duration of the spark. In the case of Tesla's circuit, we have the continuous pressure from the high voltage generator to insure the unidirectional discharge of the capacitor, and a magnetic field across the spark gap to blow-out the current as soon as it appears. The duration of the spark can be determined by both the strength of the magnetic field across the gap and by the size (capacitance) of the capacitor. In the case of Gray, we know that he was using very large capacitors, so he wasn't discharging the entire capacitor at one time. But his circuit was performing two functions: the resistor, # 30, limited the current in the discharge, and the vacuum tube, # 28, could not only shut off the discharge at whatever pulse duration he desired, but it also insured that no reversals of current appeared in this section of the circuit. So, again, all the necessary features are present.

- Next, both circuits have what I call the "Preferred Location for the ElectroRadiant Event." In Tesla's case, it is "two turns of stout wire," ("A") as he calls it, which is the primary of his electrical transformer. But as we know from reading Mr. Vassilatos, this is not a magnetically inductive transformer. The magnetic coupling is very weak between the primary and the secondary coils. In fact this device runs on what Tesla refers to as his new "electrostatic induction rules." In the case of Gray, the preferred location for the ElectroRadiant Event is what he calls his "conversion switching element tube," # 14. This component is clearly an electrostatic device, as we read earlier. It is specifically designed to have an explosive, electrostatic event radiate away from its central member.

- The next common element is the "Preferred Means to Intercept the Electro-Radiant Event." In Tesla's case, it's the secondary coil of his transformer, "F"; this is the conical or spiral shaped coil that Vassilatos mentions and that we've already seen in his patents. In Gray's case, it's the charge-receiving grids, # 34, that collect the radiant voltage. It's important to see that in both of these circuits, there is no direct connection between the source of energy and the "receiver element." Only the induced electroradiant charge appears on these output components.

- The next element is the "Connection to the Preferred Output." In Tesla's case, the output is the connection to the ground (E) and the elevated capacitance (E) that constitutes his World Broadcast System. In Gray' case, the output discharges from the "charge receiving grids" are directed to the inductive load, # 36. This element can represent either the jumping magnets or a transformer output that ran his cold electric circuit or the repulsive magnets in his motor. So again, each circuit has a preferred means to intercept the Electro-Radiant Event and a preferred method to connect it to the output.

- And finally, Gray was able to reconvert some of this excess energy back into ordinary electricity, and recycle enough of it to actually recharge his battery, as we read earlier. Tesla was not concerned with this recycling process, since his system was designed to be powered by a hydroelectric power plant.

|

| Common Features of Tesla's Magnifying Transmitter and Gray's Cold Electricity Circuit |

|

| Figure 27 Common Features of Tesla's Magnifying Transmitter and Gray's Cold Electricity Circuit |

|

| Figure 28 Gray's Circuit “Schematic |

So it is clear from this analysis that Tesla's Magnifying Transmitter and Gray's Cold Electricity Circuits are, for all intents and purposes, the same circuit. They do the same things, in the same places, in slightly different ways, and they both claim to produce extremely high gains of a cold form of "electrostatic" energy in the output. Tesla's system was obviously much, much larger since he was planning to power up the whole world. Gray was only planning to power up your home or your car. But for all intents and purposes, these systems perform the same functions and release the same "ElectroRadiant" gain mechanism.

Once again, Figure 28 shows Gray's circuit "schematic" from his "Efficient Power Supply Suitable For Inductive Loads" patent. I realized, after studying this diagram for a long time, that there were a number of basic problems with the way it was drawn. First of all, let's look at component # 42. As this is drawn (remember that this is a spark overshoot device) there is a line connecting all the way through the bottom half. If this were supposed to be an actual electrical connection, it would produce a short circuit, and would not allow capacitor # 16 to charge up. So, it can clearly be seen that this part of the drawing has problems.

Next we will look at components # 26 and # 28 which are defined in the patent text as follows:

Control of the conversion switching element tube is maintained by commutator 26. A series of contacts mounted radially about a shaft or a solid state switching device sensitive to time or other variable may be used for this control element. A switching element tube type one-way energy path, 28, is introduced between the commutator device and the conversion switching element tube to prevent high energy arcing at the commutator current path.

If the commutator, # 26, were a solid state device, there would be no "arcing" to prevent. Therefore, the stated purpose of # 28 in the patent text is misleading. However, component # 28 is described as a "one-way energy path." Gray is specifically saying that energy in this section of the circuit can only be allowed to move in one direction. This is the important condition to establish, because it is in strict compliance with the conditions Tesla set forth in order to create the "ElectroRadiant" event. There is also another glaring omission in connection to component # 28. The control grid in this triode device is not attached to anything, and that, of course, is what could control the timing of the spark discharge. In the patent text, there is no mention of how component # 28 functions and no mention of how the grid is controlled. Recognizing that component # 28 had no means of being controlled was an important realization for me.

The next problems I found were in the inductive load, component # 36. The first is that # 36 is described as an inductor but is not illustrated by a coil symbol as we see with components # 22 and # 66. Second, there are also two odd arrows associated with this component. The patent text implies that these may actually be two coils that repel each other to produce mechanical work. With this in mind, the arrows may represent the idea of two members deflected away from each other in some way. This is not made clear in the patent text. Third, we don't see any real current path through this component, so we don't know where the discharge goes. And finally, fourth, the circuit comes to the second capacitor, # 38. In the patent text this component is described as being a part of the recharging mechanism. However, none of these component connections make any sense. For instance, if impulses coming from the inductor, # 36, start charging up capacitor # 38, there are no circuit connections shown that would allow it ever to be discharged. Therefore, because of these omissions, I came to view this section of the circuit more as a block diagram than as an actual schematic.

I came to the conclusion that all that is really apparent is that the charge receiving grids are in relationship to the inductive load, which is in relationship to the receiving capacitor, which is in some relationship to the recharging of the battery. Therefore, this section is a block diagram, merely indicating that these components are in relationship to each other, rather than showing exactly how they are wired together.

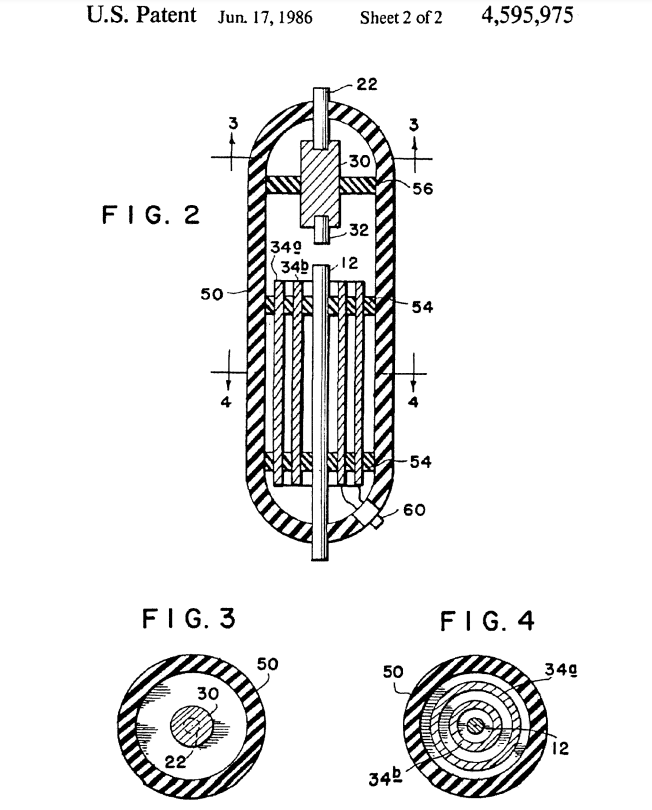

As we move towards a more complete understanding of what Gray's schematic diagram may actually look like, we will now turn our attention to his "conversion element switching tube" (Figure 29). This, finally, is the heart of the matter, the component that Gray always referred to as the "super secret means of generating and mixing static electricity." This is the element where the free energy is generated and collected.

The conversion element switching tube is really three components in one. It consists of the resistor # 30, the spark gap (the space between # 32 and # 12), and the area surrounded by the charge-receiving grids (# 34a & # 34b). Even though it is not stated in the patent text, we do know that the spark-gap is rated at about 3,000 volts, based on statements made by Gray in the newspaper articles quoted in Chapter 1. The rear extension of what Gray calls his "high voltage anode" (# 12) is the surface from which the Electro-Radiant event will be projected. This free energy blast will radiate away from # 12, perpendicular to the flow of current in the path of the spark discharge moving down that surface. The material composition of # 12 is represented as being relatively thick. It is not just a wire. But what are its characteristics? The patent doesn't describe them. We might hypothesize that this material is a bare metal with no insulation on it. It could possibly have a mirror finish, made of stainless steel or a non-magnetic material. A wide variety of options need to be tested here, but very possibly the element's diameter could be an important factor, as well as whether or not it is solid or hollow. These questions need to be explored and remain among the only unknowns.

The concentric receiving grids (# 34a & # 34b) around # 12 are designed to intercept the electro-radiant event. As indicated before, the patent states, "This element utilizes a low voltage anode, a high voltage anode, and one or more electrostatic or charge-receiving grids." This drawing clearly shows two charge-receiving grids. In the section from Gray's patent, which refers to this component, he says:

The shape and spacing of the electrostatic grids is also susceptible to variations of application, voltage, current, and energy requirements.It is the contention of the inventor that by judicious mating of the elements of the conversion switching element tube and the proper selection of the components of the circuit elements of the system, the desired theoretical results may be achieved. It is the inventor's contention that this mating and selection process is well within the capabilities of intensive research and development technique.

I'm sure this was his very nice way of saying, "This is all I'm going to tell you, but you can probably figure it out if you know what you're doing." Then he says:

The preferred embodiment of this invention merely assumes optimum utilization and optimum benefit from this invention when used with portable energy devices similar in principle to the wet cell or dry cell battery. This invention proposes to utilize the energy contained in an internallygenerated, high-voltage electric spike to electrically energize an inductive load, this inductive load being then capable of converting the energy so supplied into a useful electrical or mechanical output.

|

| Figure 29 Grays Conversion Tube Diagram |

|

| Figure 30 Edwin Gray and His # 6 Motor Prototype |

Here we have clear statements by Gray that the conversion element switching tube is the source of the useful outputs. In fact, this component is what powered his magnet popping experiment; this is what ran his circuit, that ran the TV, radios, and light bulbs, and this is the component that ran his motor. This is the element where the energy is both magnified and characterized as "cold electricity." Henceforth, I will refer to this structure as an "Electro-Radiant Transceiver", because it is designed to both broadcast and receive the "Electro-Radiant Event."

|

| Figure 31 Edwin Gray and Fritz Lens in 1973 |

|

| Figure 32 Gray's Inductive Load |

This, then, is Gray's “inductive load.” This is how he is harnessing the energy from the charge receiving grids of the conversion element switching tube, enabling him to do real work.

|

| Figure 33 Tesla's Radiant Energy Method |

|

| Figure 34 Probable Schematic for Gray's Cold Electricity Circuit |

|

| Figure 35 Paul Baumann's Testatika Machine |

|

| Figure 36 Testatika Machine Lighting a Light Bulb |

Note 1. Peter A. Lindemann attests that incandescent bulbs and other electrical appliances are getting cold when consuming "Cold Electricity".

- 🔹 Radiant energy

- 🔹 AC generator - Free Energy

🔹 Tesla Technology and "Free Energy" in practical application